WORDS BY JOEY LAGOS

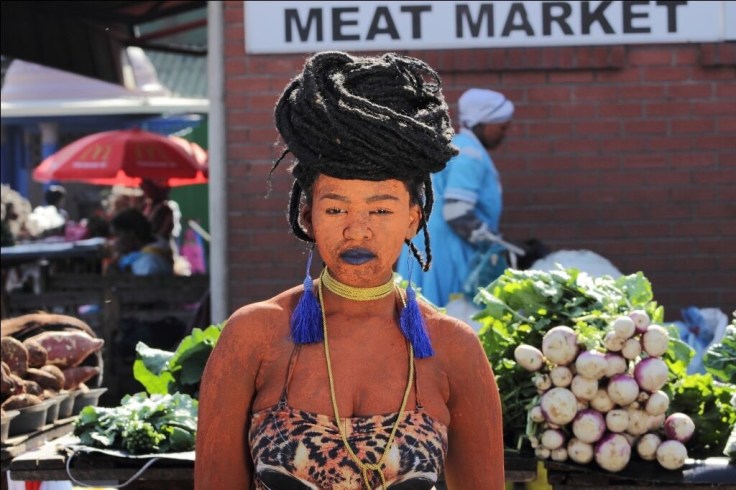

I first met Selloane in 2003 at tertiary. We were still fragile beings back then. Our attire very teenage. She mostly dressed exactly as she is in one of her oldest and one of my favorite pieces “Basotho Barbie”, a fitting title for a self-reflexive portrait by a student artist at that age. She always dashed across the courtyard, wearing a repellent look on her face. You could only just stare at her, admire and wonder. She wore dreadlocks and was to me naturally fascinating. I thought she was cold but in a fragility masking type of way. I saw through that shield however, but, I will not indulge you on my shoddy and instantly and constantly rejected attempts to serenade her with my famously seductive intelligent conversation. Since those days, many bottles of wine, Phumla’s bankies and other friendship trysts later we are here, both artists and independent individuals, with a large circle of mutual friends, a common love and hate for art, music, wine and social media.

Her artwork has fascinated me for as long as I can remember. As with any artist, techniques and philosophical prerogatives change and develop to precision with the years. This change and evolution is usually influenced by a milieu of personal and socio-political and economical impositions or realities.

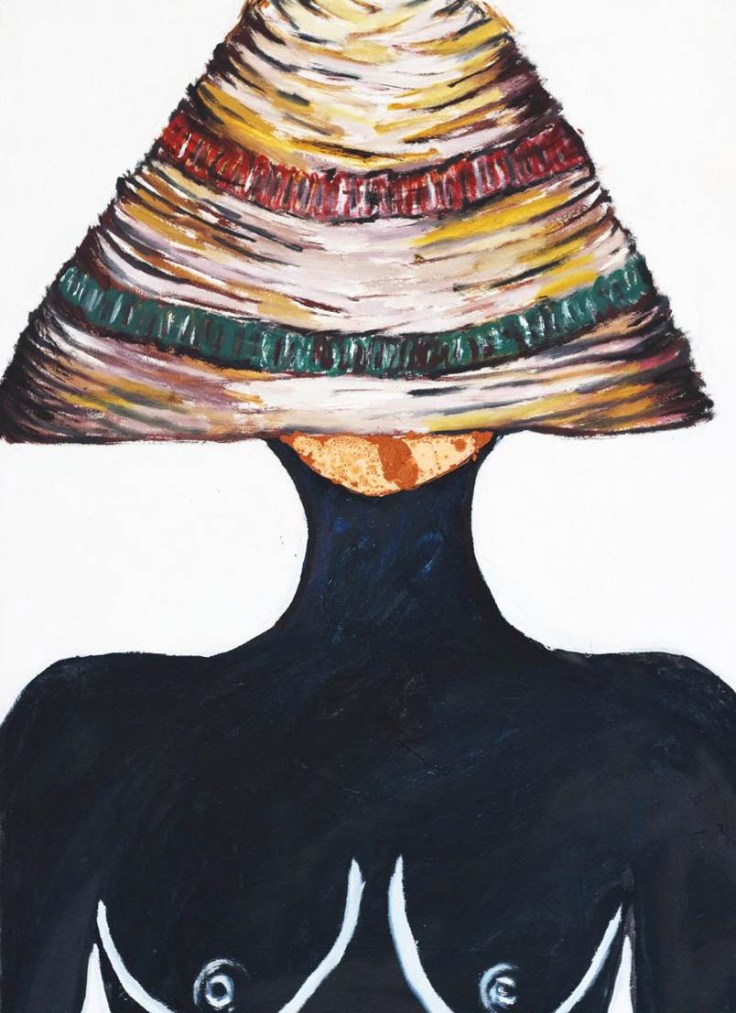

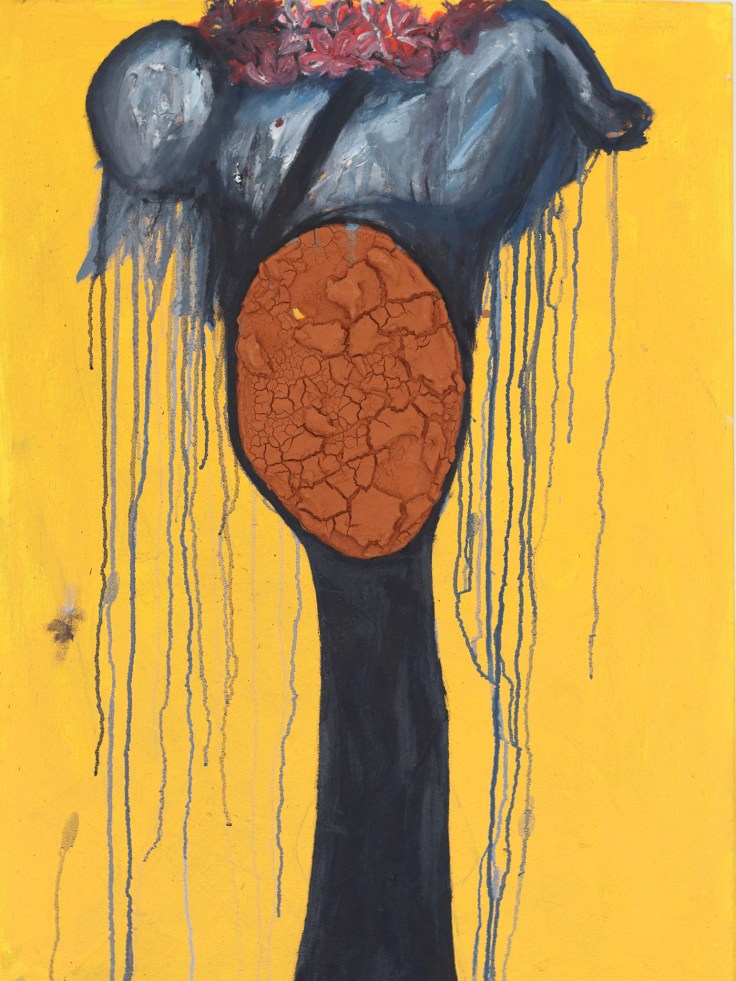

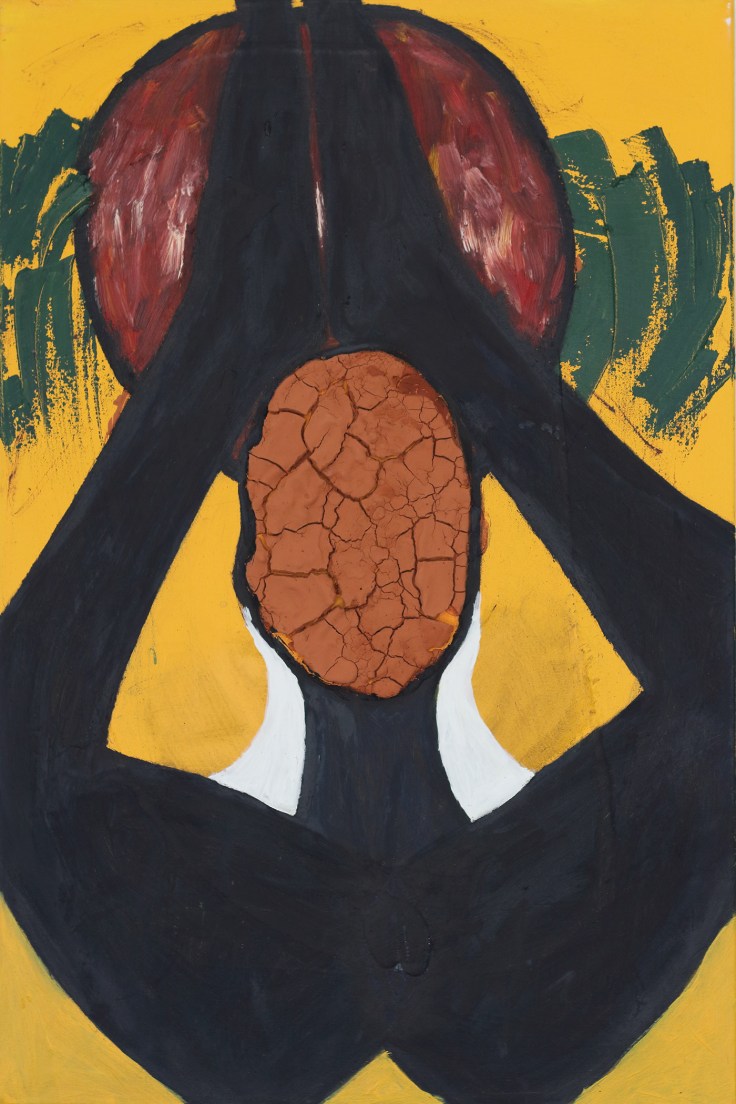

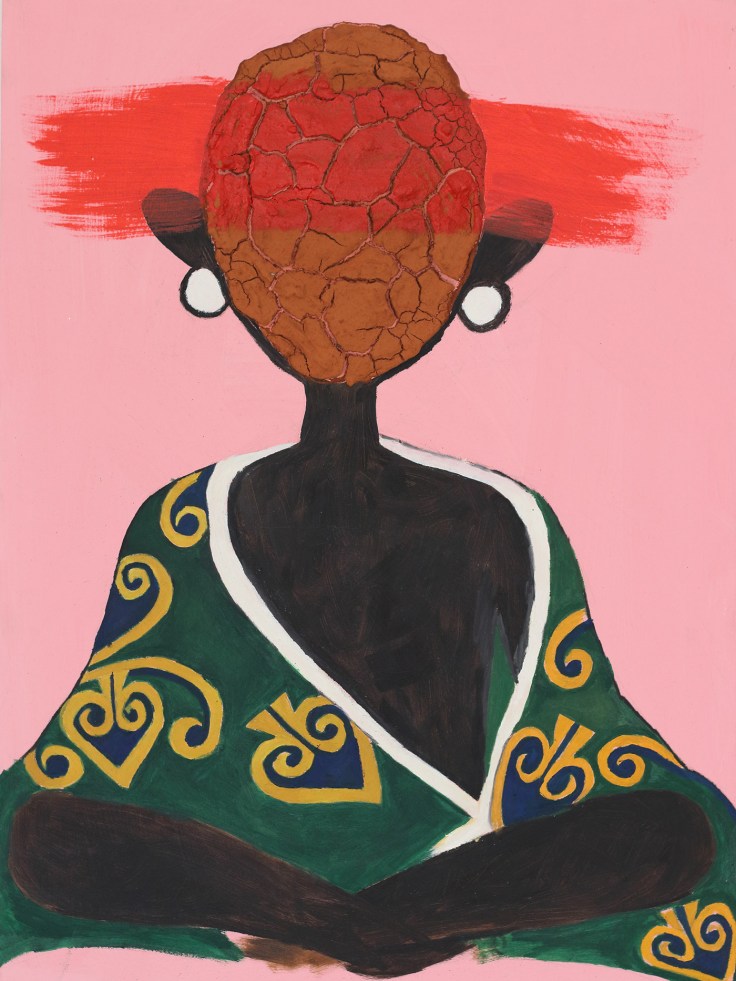

What is most striking, is her use of “imbola” (red clay) around naked women’s bodies or faces including her own. The use of red clay in Nguni cultures has spiritual and ritualistic implication. It is used by newly initiated sangomas, and in Xhosa and Sotho cultures it is used by young initiates returning home from circumcision school. It symbolizes rebirth and is also used as a fortification against exterior forces that may seek to harm the still fragile spirit or soul of the initiated/newly born. In this transformation one undergoes a rite of passage in which they shed old skin and unload old baggage in order to become anew.

I find Selloane’s work to be both a seduction and a vexation of the mind. It seduces your senses, allows you to speculate on its meaning, its intended message and then vexes your intellect, because just as you think you have it pinned down, such as the abyss it is, it gazes back. It is therefore always better to ask the artist herself.

What, if anything, informs your process if you have a process?

I start by a voice recording my concepts. Then conduct my research while I sketch, before transferring to the canvas or performance piece.

If I am right, what fueled the transition from your earlier traditional work towards the abstract use of imbola?

Earlier in my work I managed to get caught up within the politics of the industry, I was too young to know who/how/what. Then my paths lead me to fashion and styling space for a good 4 years. It was a deliberate move cause I felt my concept and work were bigger than me at the time and was not mature enough to articulate them as I can right now.

So when I returned to the Visual art industry I was less fearful of portraying the pain and spiritual conflict I was dealing with. I started to include my personal traumas of physical, psychologically and spiritually displacement as a Basotho woman. I am now acknowledging my purpose; I have started to question culture, family dynamics. I have made sure I am releasing and unlearning of the old, that is where the use of red clay came from. I am becoming.

Traditionally Imbola has very specific uses. What does it represent in your work?

My body of work speaks loudly about personal cleansing, dislocation and relocation while investigating the gender roles within the cultural boundaries of a Sotho woman born in KwaZulu-Natal. As you know in our culture ibomvu has been used as a representation of becoming used for spiritual and physical purification.

In the past 4 years I have also seen you begin to venture into performance, just as much as you paint. What inspired this shift?

I started painting to tell stories, whether the stories disturbs or comfort my audience that was not my concern. I started performing in 2017 by invading public spaces, so the shift was inevitable. I feel before my paintings start relating socially or politically they start with me, my experience, my subconscious mind, and my spiritual connection with my ancestors. I paint from pain which it’s something I’ve been avoiding to admit. It became a natural move for me to start performing, my heart became so heavy and I wanted to heal, I didn’t feel I was doing justice to myself by only portraying painful experiences. I wanted purge and I did that through performance. Performance for me it’s where I allow the public to engage, I become vulnerable in my healing, I allow them to go on a journey with me.

The performances I have seen carry very ritualistic injections, do you not fear to delve into the spiritual realm. As you know, if you gaze at the abyss for too long it gazes back…

Whether it’s a painting, installation or performance I rely a lot of on shifting energies. So yes, I am aware my work carries imoya. My late grandmother was Umthandazi (spiritual healer) when she was younger and my mother is blessed with a gift of premonitions through dreams and heals through prayer. Through years of creating I’ve realized I’ve used myself as a subject and a conduit or vessel between the two worlds. I’m very much aware I am spiritually sensitive being. Currently it’s something I struggle with understanding fully, but it’s an energy filled journey I’m not really sure where it’s taking me.

Follow Selloane Moeti:

https://www.instagram.com/blk_peach/

https://blkpeach.wixsite.com/mysite